Orienting Toward Becoming the Change You Wish to See

What do we want? Change!

When do we want it? Now!

The last post in this series outlined how if we want to enact change in our lives we’ve got to establish an embodied foundation where we feel safe; we’ve got to adopt a beginner’s attitude; and we’ve got to let go of what we think our process and/or our outcome should look like.

But now what? We could sit around all day pondering these things without moving a muscle. That practice alone could be considered a kind of meditation, beneficial in and of itself.

But what does this look like in action? The Alexander Technique is meant to help us find more freedom and efficiency in all our daily activities. So let’s look at how we can practically apply what we’ve learned so we can live the questions in a way that helps us do what we want to do better.

Stop ---> Release ---> (Re)Direct

Stopping

Where Am I and What Am I Doing?

Similar to many ancient traditions, we practice stopping in the Alexander Technique. This literally means stopping whatever we’re doing, quieting down to locate ourselves in the present moment, and noticing “what is” without judgment. This interrupts our habitual patterns, rhythms, cycles, and grooves, creating openings for us to become aware of and experience something new. It’s helpful to practice this lying down as a primer for other activities (try it for free here), but you can do it in any position at any time: mid-keystroke at your desk, mid-chew at lunch, or mid-stride down the street.

Noticing “what is” in the Alexander Technique means becoming aware of things like the shape of our bodies in space; noticing what our muscles and bones are doing; noticing our involuntary processes like our heartbeat, breath, and digestion; observing our thoughts and feelings all as objectively as possible.

Releasing

Can I do less?

Out of this quieting down and noticing where we are in space, and what we are doing, then we become curious about what we no longer need so that we might release it. Where in your body are you working harder than you need to work? Can you use less effort to carry out the activity you’re doing right now? As a somatic practice, the Alexander Technique approaches release through our muscles first. This may at times indirectly lead to other releases in our thoughts, emotions, and breath patterns as well, but we are always circling back to our musculature. We release the muscles of our neck and shoulders, then our back, then our arms and our legs.

(Re)Directing

Where do I want to go?

A lot of practices end at the stopping and letting go of extra tension, which can be useful since many of us are so stressed out and overly tense that specific times set aside for releasing are the only way we bring it into our lives. However, since we’re interested in applying this to our daily activities, we go one step further in the Alexander Technique.

We release to more fully receive the support of the ground, and then we direct that support; we guide it in a specific way to choose where we want to go.

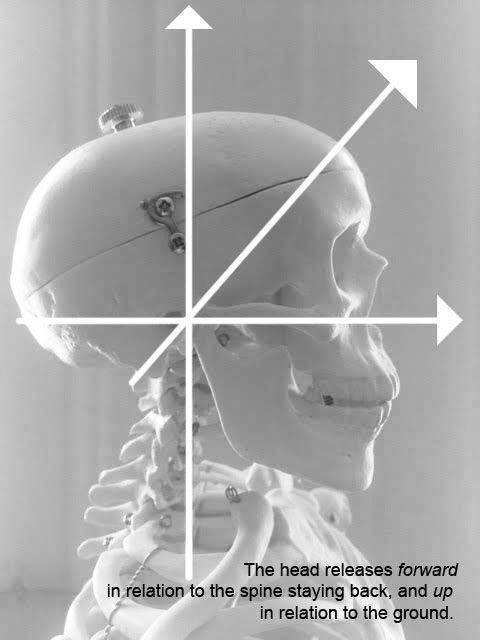

With the release of our neck, we aim our head away from the top of our spine in such a way that it encourages our entire back musculature to expand. The classic Alexander directions say to let our heads go “forward and up”. When our overly tight neck muscles undo into length, our head will naturally rotate forward in relation to our spine staying back. The majority of the weight of our skull is in front of our spine when our head is efficiently balanced in a neutral stance.

The “up” part of “forward and up” means we are directing our head away opposite the ground underneath us. If we habitually tend to slump, there will be an actual moving up through space; our head will literally lead us from one plane to a slightly higher plane.

If we habitually hold ourselves rigidly upright, we may not need to move up through space. Rather as we undo our extra tension and allow our weight to pass through to the floor, the upward direction comes back through us as if the tops of our heads were opening to let the support of the ground go out through our skulls. It’s more of an energetic up.

(Note: In order to practice this part, you need to know that the top of your spine is all the way up between your ears. When your neck muscles release, you want your head to nod forward from there. If you don’t think of your spine as that high up, your cervical spine will get drawn along into the forward direction, which we don’t want. I also would like to mention again that trying to describe this process without the hands-on guidance of a certified teacher is very difficult since we need someone to help us identify what we may be missing. It’s truly a unique embodied experience, and I recommend finding a teacher near you for a series of lessons if you have any inkling this work may useful for you.)

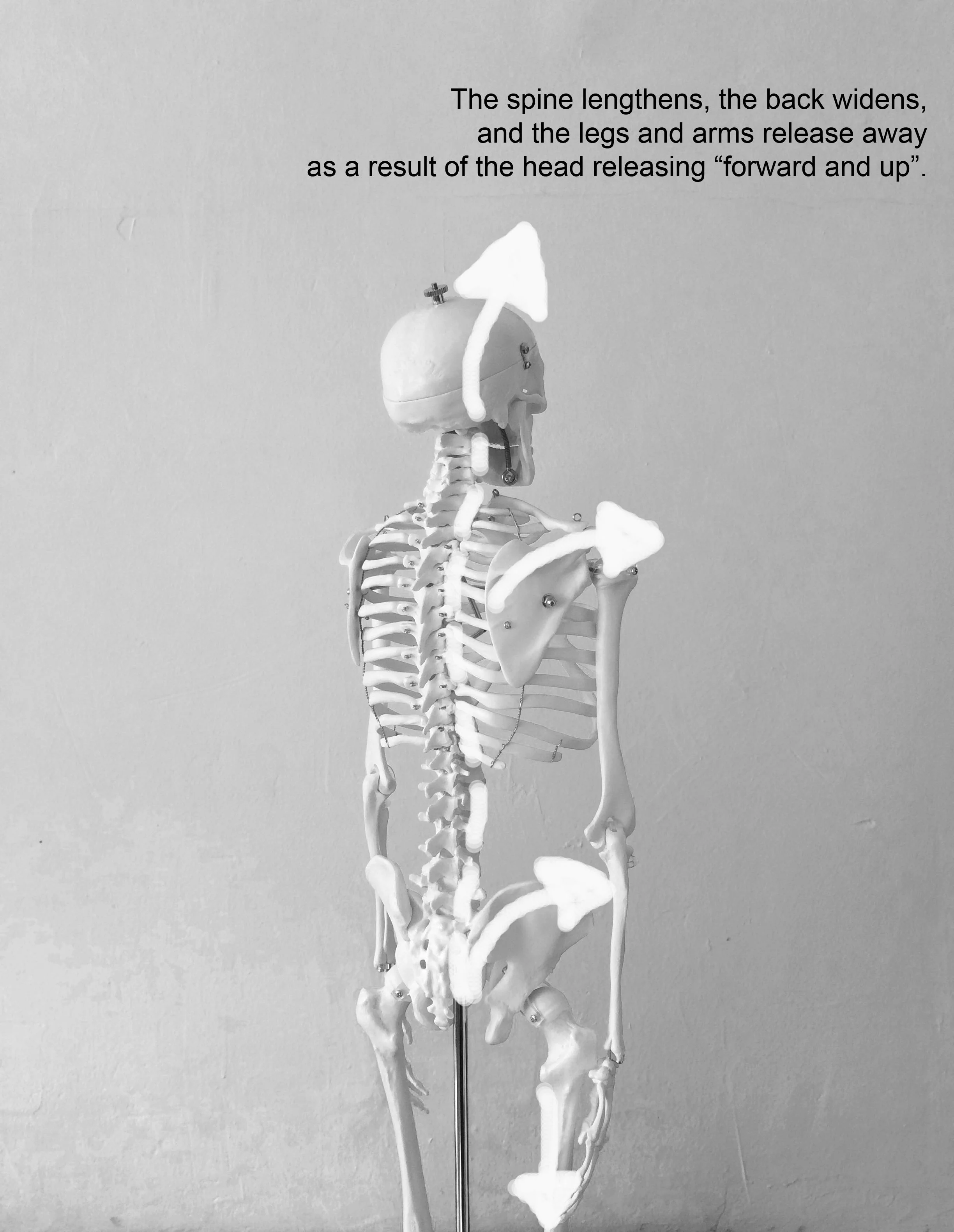

Directing the head forward and up is not a “pulling up”, nor is it an isolated event, nor is it a correct position to find and lock. Often times when we think of going up, we over lengthen: unhelpfully straightening the curves of our cervical spine, tucking our chins, and sticking out our chests to throw our shoulders back, which immobilizes our thoracic spine and our ability to breathe well. So in order to ensure we are not over-lengthening, the directions of sending our head forward and up cause our spines to be drawn into length, and our backs into width. We widen through our shoulder and pelvic girdle. The lengthening and widening are interdependent on each other for the kind of balanced expansion we seek. Rather than a position, it is a new relationship of your head to neck to back.

As all this is happening we also direct our legs away from our torsos through our feet, and our arms out of our backs through our fingers. These directions deserve more attention, but for the sake of length and keeping this post focused, we'll leave it at that for now.

In a sound bite we are thinking Forward, Up, and Out.

You might think of it as akin to cultivating the inner smile referenced in Buddhist meditation. It’s our inner smile that grows so strong as to have an effect on our muscles and bones-- our posture. When we use this process in our daily activities, the benefits extend way beyond the physical. We never know what the future will bring, but we can consciously choose the direction we want to head in to meet it. Learning to go forward, up, and out in response to world gives us a template for becoming the change we wish to see.